Nyhet

Students and Power in Zimbabwe – The stepping down of Mugabe

For the first time since the wave of demonstrations against the authoritarian regime of Robert Mugabe in the late 1990s, thousands of citizens marched to the streets to protest: students, social movements, civil society and ordinary citizens demonstrated various reasons such as academic freedom, decent jobs for graduates, democratic participation, peace, freedom of expression, proper service delivery, rule of law, the stepping down of Mugabe and the fall of Grace Mugabe among other factors. However, the ultimate reason which brought all these forces together was the demand for the step down of Mugabe. Thus, Zimbabweans joined the worldwide wave of changing democracies spearheaded by social movements, some which were characterised by active student leaders. Of course, each of these movements originated and developed differently. This article serves to discuss the role played by students in challenging the power holders in Zimbabwe with focus on the fall of the 37 years ruling president Robert Mugabe.

The enduring culture of protests by students against governments can best be summed up by Karl Marx’s observation that the history of society is indeed a history of class struggle. In a way, students view themselves as a class, with a special identity, place and role to play in society. The starting point for judging this university class should be its academic prowess in terms of generating and contributing to the advancement of knowledge. An inevitable product of this knowledge and enlightenment is in most cases the desire to bring change to the status quo in society. In the same vein, student politics in Zimbabwe have mirrored the national politics of the day to some extent.

Now let us look at the historical background of the Zimbabwean students and how they challenged the autocratic regime. The first decade after independence (1980) was a honeymoon period in the relationship between government and students. Students received grants and loans from the government and had much influence in government planning and policy implementation. The government then in the 1980s immediately declared a Marxist-socialist ideology and a leadership code which meant that the government effectively responded to the peoples’ needs. This was a more democratic period for the governance of Zimbabwe. In this period, the government was inclined to treat students with care and respect in order to prove that it was different from the colonial regime. Another interesting issue to note is that the euphoric crowds which celebrated independence included graduates from the university and those from foreign universities who had come back to assist in rebuilding the new born country.

Unfortunately, this honeymoon did not last for long as relations between students and the government began to sour with the capitalist system which came in place around the late 1990s. The Amendment Bill currently referred to as the ordinance act was introduced in 1983, on the 14th of January 1983 was when the act commenced. The Bill curtailed academic freedom and was, and is still, strongly resisted by students. Of interest in the Bill are rules on student conduct and the powers vested in the university vice-chancellor to discipline students. A section of the Bill empowers the university vice-chancellor to discipline students deemed to have disrupted normal business on campus. It also empowers the vice-chancellor to suspend any student or staff member as deemed necessary pending a disciplinary hearing. This Bill has taken away academic freedom and at the same time magnified the powers of the vice-chancellor. Students, on the other hand, felt that they had a right to speak out on issues affecting society.

Some of the important issues to note as we look at the nexus between students and power in Zimbabwe are the ideologies and activities carried out by the student movements. Student movements considered themselves at the vanguards of democracy, despite the fact that the institutional authorities were viewing them with suspicion. Students within the ecumenical movement also strategically used the ecumenical approach to create sustained dialogue with authorities. Students used social media as a tool for promoting participation among youth in challenging autocratic practices using the provisions of the current constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) Act 2013, chapter 4 the Bill of Rights section 61 which notes that every person has the right to freedom of expression, which includes a) freedom to seek, receive and communicate ideas and other information, b) freedom of artistic expression and scientific research and creativity and, c) academic freedom. It is however sad to note that there is still a lot to be done to ensure absolute change. Also, on a sad note there is still need to ensure increased female participation in student activism as there is still limited female participation in student politics even at national level. The inclusive formulation and implementation of an education policy that ensures academic freedom for students in Zimbabwe is one of the major concerns still affecting students.

Fortunately, there is always light at the end of the tunnel. Students in Zimbabwe are still celebrating the work they are doing and that done by former students who were victimized, tortured, harassed and arrested in an effort to demand democracy. We look at the likes of Lenmore Judah Jongwe, Brighton Makunike, Douglas Tigere, Pride Mkono, Sally Dura, Jestina Mkoko, to mention but a few. The fall or rather step down of Mugabe was a motivation and inspiration to the Zimbabwean student movements as it strengthened their hope for change in the education sector.

The Mugabe regime symbolised an unquestionable governance structure. Almost every institution was politicised and manipulated by the state security forces to protect the interests of the regime and the powers of R.G Mugabe hence posing a barrier for sustained dialogue between the students and the institutional authorities. Thus, making the fall of Mugabe a dawn of a new era with a lot of uncertainties. This especially considering that the current president (Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa) was also a strong force in the Mugabe regime. However, as a president seeking for legitimacy from the people of Zimbabwe and the international community he is most likely to make himself favourable to both that above-mentioned groups by respecting and positively responding to the needs and demands of the people of Zimbabwe.

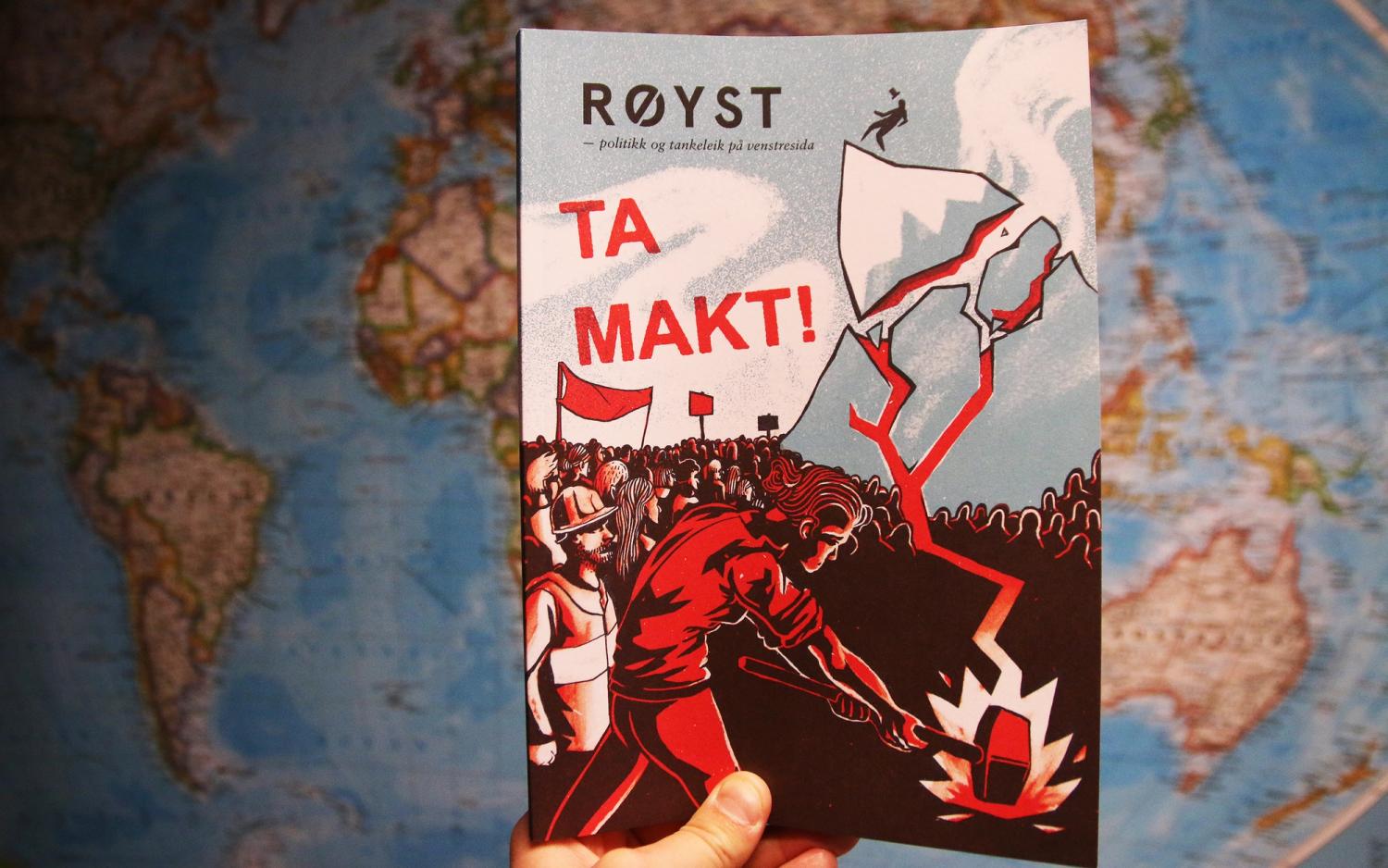

This text was originally published in Røyst #9, 2018. www.røyst.no